I frequently prepare valuations of interests in privately held companies for divorce. Over the years, these cases introduced me to many attorneys and valuation experts and led me to what I call the Three Business Valuation Truths.

Truth #1: Only Advocate for Your Opinion

Attorneys serve a vital role as advocates for their clients. This is mission-critical, especially in situations where one side may be at a real disadvantage financially or emotionally. Business valuation experts also play a vital role in litigation; however, they should not, in truth must not, confuse their role with that of the attorneys. Attorneys advocate for their clients. Experts only advocate for their opinion.

What do I mean by this? Consider the unfortunate situation where a divorcing business owner retains counsel and counsel retains an expert to determine the business’s fair value. Understandably, the business owner may want the lowest possible value for the business. Counsel retains a business valuation expert and instructs the expert to value the business as low as possible. The appraiser complies by taking a path through the valuation process, selecting assumptions that nudge the value lower and lower at each turn. Counsel for the non-owner spouse also hires a valuation expert, instructing the appraiser to arrive at the highest possible value for the business. Both appraisers, viewing the roles accordingly, oblige and submit reports a million miles apart. Thousands of dollars in additional appraisal and legal fees later, no progress has been made toward reaching a settlement. Both sides are in entrenched mindsets regarding the righteousness of their positions. The matter goes to trial, and a somewhat disgusted judge simply splits the value down the middle.

Sounds familiar, does it not?

Unfortunately, we live in a world where the Hired Gun business valuation expert is a reality. More unfortunately, the compliant appraiser may be more of a rule than an exception. So, why should we all aim to change this in a world populated by Yes Men and Yes Women?

- Hired Gun appraisers give the whole valuation industry a negative reputation. Judges, mediators, and arbitrators face a vast expanse of issues in divorce cases. Business valuations often present fact patterns requiring highly specialized, nuanced, and complicated analysis. When the folks who need to rely on a value do not find comfort in the information presented by wildly different positions, it creates a gulf in trust.

- Biased opinions create risk for triers of fact. If an appraiser tips the scale one way or another, this creates exposure and the possibility of excluding a valuation expert.

- Human beings are subject to anchoring bias. This means that we tend to latch onto the first information we receive. Moving toward more balanced settlements becomes difficult when appraisers present unrealistic values, thus setting unrealistic expectations. This may add to costs and conflict.

- Case law reflects the inputs judges are forced to consider. When we complain about unappetizing valuation case law, let’s recognize that it may be the by-product of appraiser bias.

A few weeks ago, I arrived at a meeting among both sides’ attorneys and business valuation experts, not knowing who might be sitting across the conference table. I was happy to see a fellow appraiser whose professional ethics and values I trusted. I had zero expectations that we will agree on everything during the course of this litigation, but I also did not expect the time-wasting valuation shenanigans routinely encountered elsewhere. What did this mean to attorneys and their clients? The mutual trust between the experts took some of the rancor out of the room. That alone helps move matters along more efficiently.

In a separate case a few years back, the opposing side proposed a value dependent on the repeat performance of one very good year. The data might have supported this on its face, but a trail of non-recurring items was buried in the financial records. Counsel approved a conversation between the experts to bring attention to the information on both sides. In this case, the opposite party’s expert, rightfully perturbed at the information not being called out at the onset, used the data to illustrate why the value, and funds for support, needed reconsideration. By being open to a process that required reconsidering his opinion and not simply digging in his heels as a client advocate, the other appraiser quickly turned down the heat and brought both sides closer to a fair settlement.

We all play key roles in matrimonial disputes, so attorneys advocate diligently. Your clients need you. As for the valuation professionals, we, too, should be advocates of our opinions. Everyone benefits when the Hired Guns hang up their hats and become trusted advisors.

Truth #2: Valuation is Inherently Forward-Looking

The second Valuation Truth bomb I’ll drop concerns valuation methodology. Legal professionals tend to be most familiar with the income approach, specifically the capitalization of cash flow method (CCF). CCF is a single-period capitalization method closely related to the multi-period discounted cash flow method (DCF. Occasionally, I hear that legal professionals perceive a CCF valuation as more reliable than a DCF because they believe that a CCF does not require a forecast and only relies upon historical data. I think it is high time we burst that particular bubble. Let’s consider business valuation truth number 2: the practice of business valuation is inherently forward-looking.

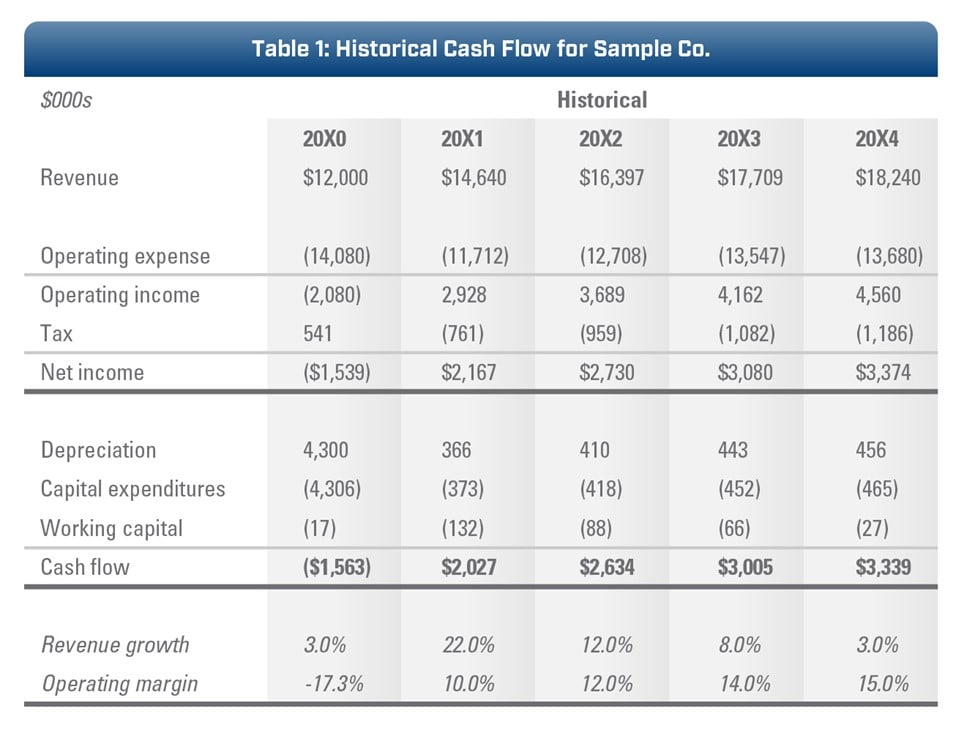

Using the old misconception that CCF is historical and a DCF is forward-looking, consider Sample Co. as an example. Sample Co.’s operating history is presented in Table 1:

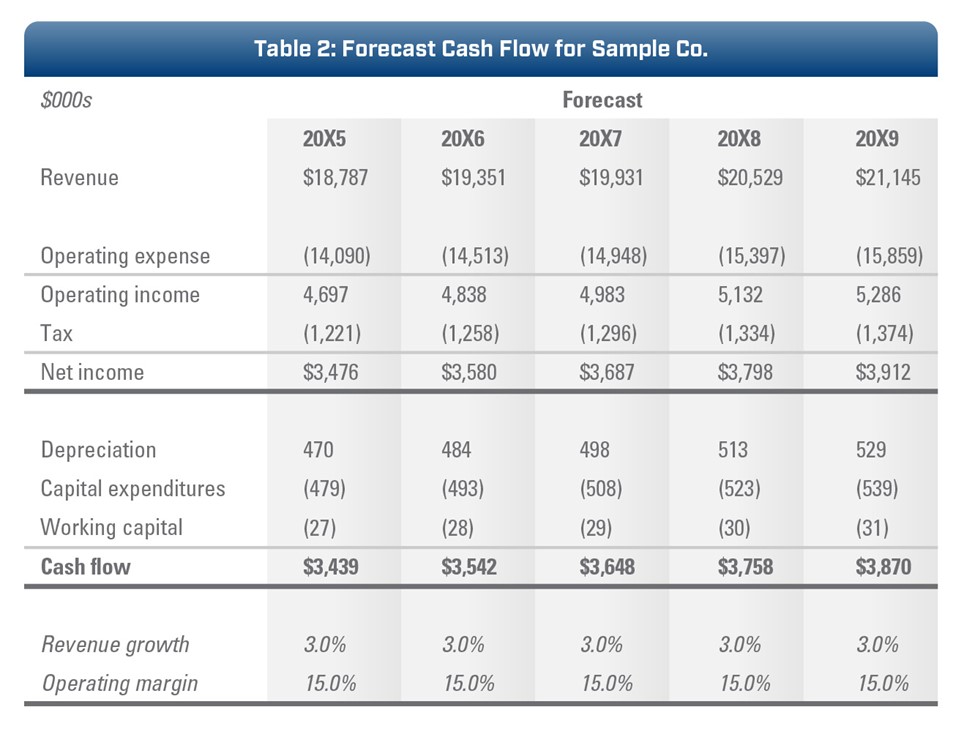

Sample Co. invested in a new production line a few years ago, spurring revenue growth that has stabilized and helped improve overall operating margins. Given the fact pattern, Sample Co. provided the forecast in Table 2.

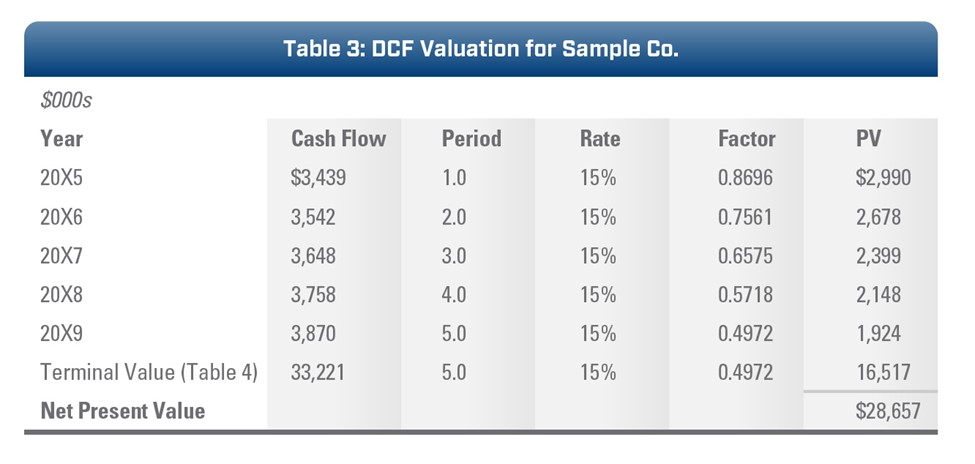

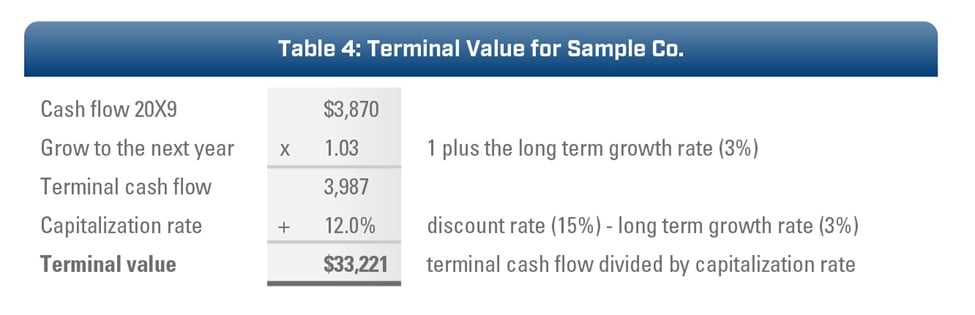

The appraiser used the forecast and prepared the DCF valuation as presented in Tables 3 and 4, concluding on a value of $28.7 million. For this example, we simplify the calculation by assuming that the cash flows occur at year-end. In practice, a mid-year convention adjustment is made to treat cash flows as though they are received evenly throughout the year.

Counsel objects to using a valuation method that relies on a forecast, especially one that presents revenue five years in the future that is 16% higher than the most recent period. Counsel expresses concern that using a forecast instead of a historical method will be too risky.

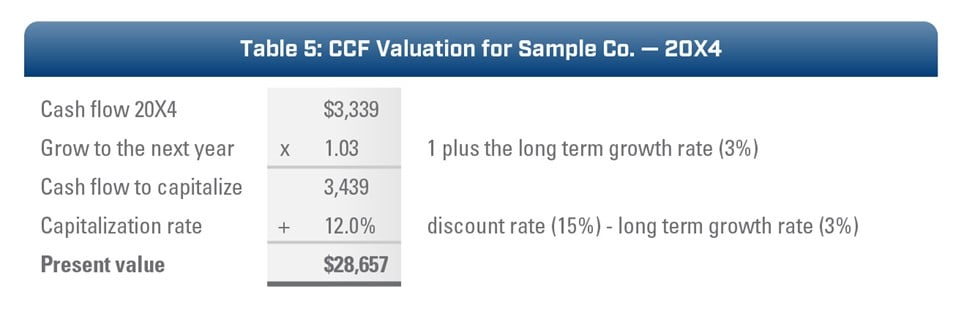

The appraiser provides counsel with a CCF valuation as presented in Table 5, which concludes on a value of $28.7 million – exactly the same as the “forward-looking” DCF. Had the previously noted mid-year convention adjustment been made, the values using a CCF and a DCF would also be equivalent.

The forecast revenue growth in Table 2 was 3% each year, and the margins were constant. In this instance, the forecast prepared by management is precisely the same as the underlying assumption of a CCF. In this CCF, the underlying assumption is that the future cash flows will grow at a set rate (in this case, 3%).

Even the CCF, with its pared-down inputs and invisible forecast, is, by nature, a statement about future expectations for a particular business interest. The underlying assumption of a CCF is that the company will invariably persist into the future (in this case, growing 3% per year), which is the same assumption driving management’s forecast. The CCF is no more a historical model than the DCF – it is structured on a built-in assumption of stable future growth. Both models are informed by history and forward-looking.

This brings us to our third truth, a concept borrowed from architecture: form follows function. Or another way to look at it: the valuation method must match the facts.

Truth #3: Form Follows Function

The architectural concept of form follows function dates back to an 1896 quote from architect Louis Sullivan from “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered” in Lippincott’s Magazine:

It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human and all things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function.

Business valuation is no different. Selection of the right method for an appraisal is a crucial part of the valuation process. Methods are neither one-size-fits-all nor applicable to every assignment. Even within one method, assumptions may differ depending on the underlying fact pattern.

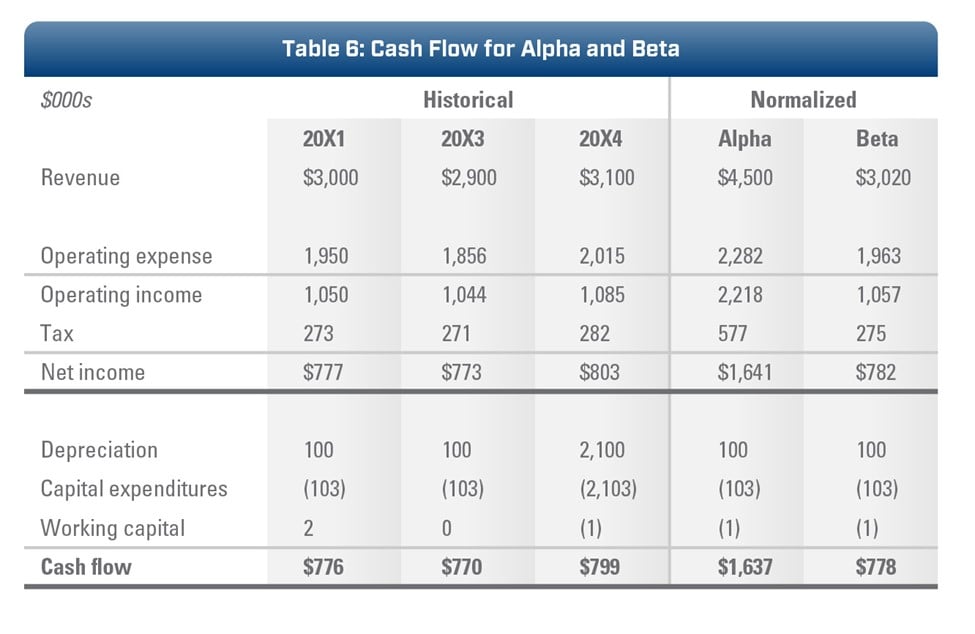

Consider a situation where there are two companies with identical historical cash flow data, Alpha Co. (Alpha) and Beta Co. (Beta). You retained Expert Valuation Firm (Expert) to determine the fair value of each company, which Expert accomplished using the capitalization of cash flow method (CCF). As a brief recap, the CCF is a single-period income approach that computes the present value of expected future cash flows. It requires three inputs: cash flow, discount rate, and growth rate. The cash flow should represent normalized expectations for the business looking forward or normalized cash flow. The discount rate should represent the relative risk of achieving those cash flows, and the growth rate should be the rate of growth in the cash flows sustainable over the long term. For this example, we are focusing on the normalized cash flow component.

As indicated in Table 1, Alpha and Beta present identical historical cash flows. However, Expert determined markedly different normalized cash flows for each company.

We will tackle Alpha first, where Expert determined that normalized cash flow is $1.6 million, based on the most recent year, which Expert deemed the most representative of future expectations.

I have heard fellow appraisers state that one must pick the most recent year because it is the closest to the valuation date and presents the most appropriate basis for the valuation. I believe that this argument grounds itself in form first. Sometimes the most recent period provides the best indication of future expectations, but that’s not always the case. Designing the valuation to fit the facts holds to the principle of form following function. Let us proceed with questioning the Expert a bit.

Attorney: Why did you choose the most recent year?

Expert: I used the most recent year because the past three years show a clear growth trend – each year keeps increasing.

Attorney:Why?

Expert: Partly due to a ton of growth in the region surrounding Alpha. Two years ago, the company committed to growth by investing an extra $2 million in capital improvements.

Attorney: How can you tell?

Expert: Capital expenditures in 20X4 are much higher than normal. You can see how that investment paid off with the last year’s excess revenue growth. I actually consider my normalized cash flow to be conservative.

Attorney: Why?

Expert: I’m only capturing the first year after that huge investment. Considering the magnitude of the amount invested, the company could benefit further.

Now the conclusion begins to make sense. A compelling narrative exists to support the appraiser’s choice – form follows function. Let us move on to Beta:

Attorney: What level of normalized cash flow did you use in your valuation?

Expert: $778,000

Attorney: Why?

Expert: I based this on the normalized average over the past five years.

Attorney: Why did you pick the average when you used the most recent period for Alpha?

Expert: 20X5 was a bit of a fluke. Beta was temporarily the sole resource in the area and picked up about $1.5 million in sales from a competitor. Without this, revenue would have only been $3 million.

Attorney: Why?

Expert: There was major flooding in the area at the end of 20X4. Beta rebuilt the damaged part of the plant – but it cost about $2M. A major competitor with huge contracts did not fare as well.

Attorney: How do you know that?

Expert: You can see the large capital outlay and the temporary revenue spike in 20X5.

Attorney: Why do you think it is temporary?

Expert: It is temporary because I only saw excess revenue in the first few months of the year. The Company paid out some overtime and bonuses because the staff pitched in to complete the extra work.

The historical profit and loss statements were identical for Alpha and Beta, but the stories behind the figures differed vastly. Valuation is not a rote exercise of performing simplistic calculations. Governing assumptions, such as determining normalized cash flow, require support. Understanding the narrative behind the numbers may provide a user of a valuation report with a better means of defending or attacking that expert’s conclusions.